↑ MouseTrap

Page Created: 4/2/2020 Last Modified: 1/4/2024 Last Generated: 3/5/2026

On March 26th, 2020, only three days after my local county issued a stay-at-home order due to the 2020 pandemic, while I was at home struggling with astrodynamics calculations to drive the orbital mechanics for my TrillSat project, we noticed signs of a mouse in the kitchen--droppings and torn-up tissue. It appeared that some little creature was performing its own calculations...

I had heard a few noises like scratching and plastic bags rustling around 3 am a few days earlier and hadn't seen any of our resident house centipedes↗ lately, beneficial arthropods that eat the more harmful insects, a sign that something else might have been eating them. We occasionally see a hawk or fox outside, but we don't have any cats to catch or deter mice, since I'm allergic to cats. However, we do have a friendly, black neighborhood cat named Maude that often tries to enter the house to my objections--sorry Maude, I'll have to deal with this one on my own.

While being isolated at home, rationing food supplies and tissues, this was extremely problematic, for the mouse could get into whatever food we had left, and it could potentially bring another deadly respiratory virus, hantavirus↗ along with its pulmonary syndrome, into the home. Famine and plague were already looming, and now pestilence had squirmed its way in.

It was as if Banksy's bathroom rodents had arrived, artwork that he curiously created around the same time during the pandemic lockdown at his home. The timing isn't too surprising, though, as two months after my incident, many news outlets and our CDC reported that the pandemic shutdown had disrupted the normal restaurant food sources for rodents, and they were now hungry and scampering into residential areas↗

I went to my local hardware store that evening, one of the "essential" businesses still operating, to look for a mousetrap, but it was under limited hours of operation due to the pandemic and had already closed at 6 pm. So I started to look at what I had on-hand to build a live trap and planned to release it far away, so it doesn't return. As of 2020, the CDC's Facts About Hantaviruses↗ brochure does not recommend using live traps for rodents, but I have never built a kill trap before and don't like the idea of doing so. We've had several Syrian hamsters as pets, and I named some of my microcontrollers after them↗.

We even keep a copy of Clinical Laboratory Animal Medicine: An Introduction, Fourth Edition (2013) on our bookshelf to aid us in keeping pet hamsters healthy, as, unfortunately, medical knowledge about "pet" hamsters is hard to find, as the most detailed information is buried in the results of scientific papers where the creature is not intended to be a pet but merely the subject of laboratory experiment for some other research domain (including studies on hantavirus). That book even includes a small section on hantaviruses on page 131 in the chapter Rats. So I am well-aware that mice are intelligent rodents that deserve humane treatment, and these mice are no different than the ones freely romping around outside, except they happened to come inside.

However, according to an article published at the CDC in 1999 in their journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, if it was a deer mouse, for example, it is not ideal to release it close to the original residence, since they will navigate their way back home over surprisingly long distances↗.

I enjoy building things like tethered robots, vending machines, electronic trip wires, and even playing DungeonCrawl and RogueLike games where I kill Giant Rats (heck, I even went to see Crispin Glover at a local college in the mid 2000s where he read from his book Rat Catching↗ ), so this project of necessity was oddly well-matched to my background, but it was definitely not much fun. In a self-similar irony, here I was, suddenly "trapped" in my own home by the pandemic and immediately afterwards found myself trapping a small animal, like Burt Lancaster's character in the 1962 film Birdman of Alcatraz.

You can't mess around with sanitation or food storage. This isn't a first world problem--it's a medieval world problem--and it's also hard to sleep knowing that something is creeping around or setting off the trap in the middle of the night. The house was built in 1936, and I felt like what I imagine people did during the Great Depression and Dust Bowl with the things they had on hand. A lot of cartoons during the depression era depicted mice... and cheese. Many people say to use chunky peanut butter as bait and not cheese, but cheese has always worked for me, just like those cartoons, and it was what I had on hand. I used to build Rube Goldberg devices in school when I was young, and loved Ideal's Mouse Trap kinetic board game, but with this project, I had no desire to convolute the process but merely tried to solve an ancient problem quickly.

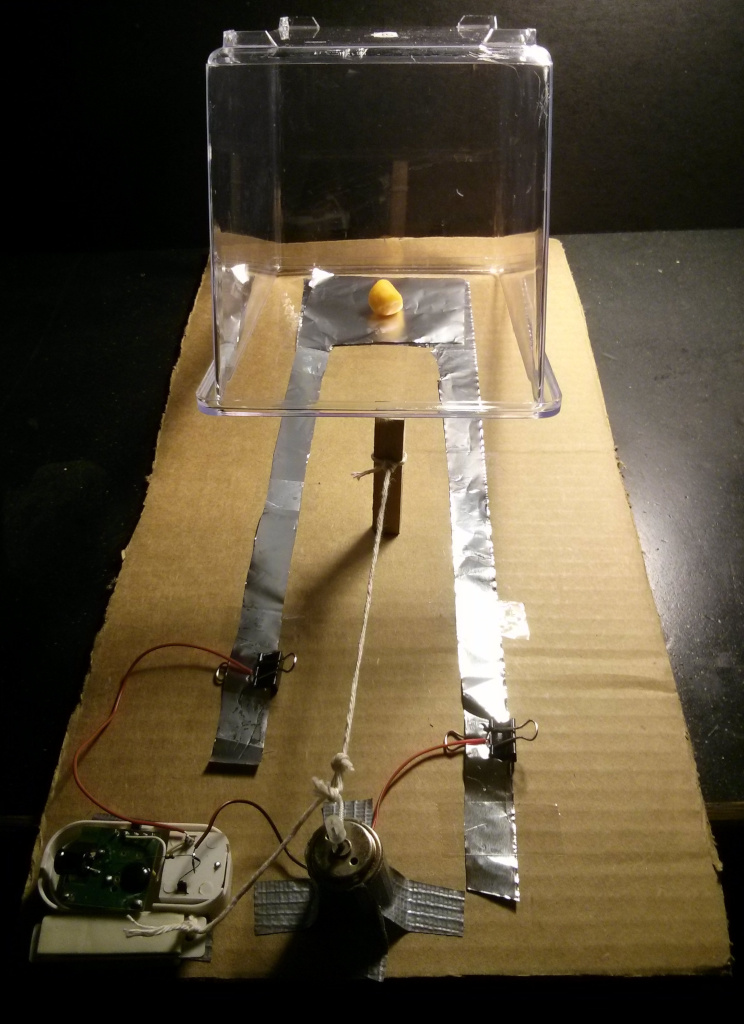

I've built a similar kind of trap before back in the 1990s (a direct, loud, vertical drop using a tape recorder motor, coffee cans and coat hangers, eschewing the stick) and have used makeshift switches in an alterate-reality game during that same time period, but I decided to simplify this design (my 4th prototype, actually) and just use a simple stick and string, like those old cartoons. It has both benefits and drawbacks, but it successfully catches the small rodent alive and also sounds a continuous alarm to let me know when it trips. This time around I also tried to seal off airborne pathways as best as I could in case the mouse was a type such as a deer mouse or white-footed mouse that could carry the virus (the virus is rare in my part of the country but the mice are not).

The Design

I used the clear plastic bin of a hamster travel carrier for the container, but any relatively heavy container would have sufficed, ideally with no air holes (more on this later). A transparent container makes it easy for me to see what animal I am dealing with before I approach it, as it's usually the first time I will encounter what is creeping and hiding around the house, but it can also scare the animal, as it can see me through the container as well, causing it to urinate, or it may even attempt to attack my fingers through the transparency (in roguelike fashion) as I approach it. So a better approach might be to keep the bin mostly opaque with a small window on top where I can see the small animal, but it can't get a good line-of-sight view of me from its angle at the bottom of the bin (also like a roguelike↗, by the way).

A scared mouse can also frantically jump and move the bin off of the cardboard and eventually wedge underneath the gap and escape, so I learned from experience that it is critical to tape down the far edge of the bin so that it acts as a hinge, preventing the mouse from sliding the bin around. (Note that the tape is not shown in the photo at the top of the page, as I added it later.)

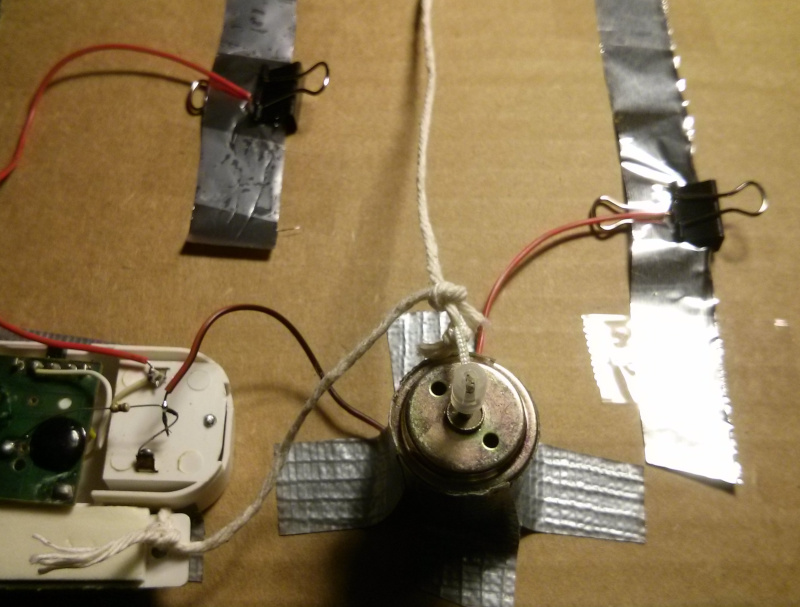

I cut aluminum foil into into two small flag-like shapes, like the flags on a mailbox, or like the state of Oklahoma↗ (curiously the same state hit hard by the Dust Bowl which inspired Steinbeck's 1930's novels The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men) with a very long "panhandle" acting as circuit traces, the pan portion acting as a pressure switch. A square of toilet paper (this stuff was also in high-demand during the pandemic) was cut as shown above to act as an insulator, with a tiny section in the center to keep the bait from activating the switch. It's like a little moat, with the castle (cheese) in the center. Clear tape was used to hold everything down and a portion was used to insulate the top of the panhandle of the top flag to prevent it from touching the bottom flag.

The flags are flattened and flipped atop one another into a foil "flag sandwich", so the top and bottom foils do not touch, and cheese can be set in the middle. It's a capacitor, really, but the capacitance is not what I'm trying to measure, just a total capacitor failure, a complete short across the dielectric is what I'm sensing. When the foot of a mouse approaches the cheese, it presses the top foil down in the moat, touching the bottom foil, to complete the circuit, triggering the motor.

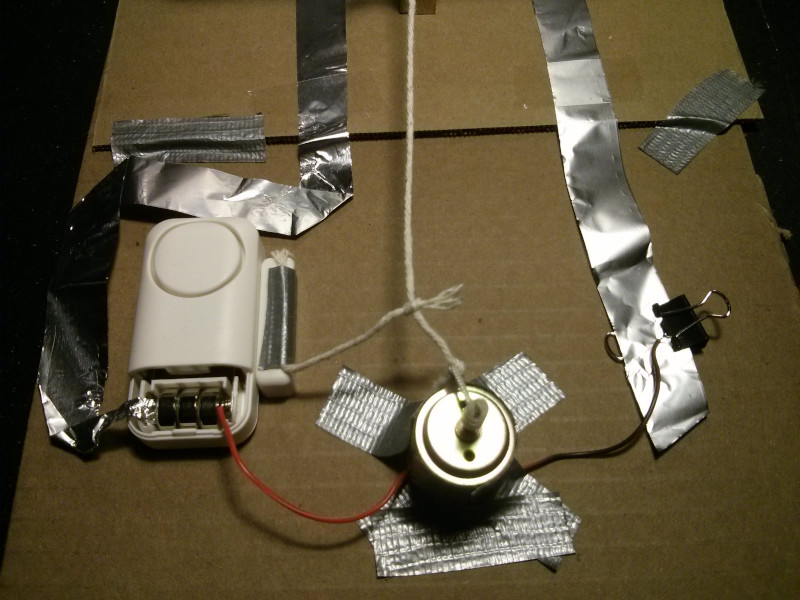

I removed a small brushed DC electric motor from an old, battery-operated device that I had used for parts, which I taped down to a cardboard platform, and it already had this little string attached to the shaft to act as an actuator, which was convenient. I suppose I could have wedged or glued a shaft and string onto if it wasn't already attached. As a power source, I simply used one of those magnetic switch, piezo door alarms that can be found at a dollar store, containing 3 LR44 batteries. I decided to open and flip over the alarm to solder to the battery terminals (since I also needed to fix the reed switch--poor manufacturing), but this was not necessary as the left foil panhandle and motor wire can be been wedged against the positive and negative terminals at the battery connector on the other side (which I did later, see below). I used small paper binder clips to clip the wires to the long foil panhandles, since soldering was not possible.

Note that the small LR44 batteries and fairly wide (about 1.5 cm) aluminum foil panhandle circuit leads are necessary to prevent a fire hazard. Larger batteries or AC adapter would be hazardous and should not be used in this design. When a mouse steps on the pressure sensor, the motor retracts and reels in the stick that holds the plastic bin open against gravity, causing it to fall. If the mouse keeps its foot on the sensor, or if the foil sensor is deformed and causes a permanent closed circuit, the motor will keep retracting and the string will bind, causing a stall condition, drawing higher current. The max current of the LR44 cell is low and will drain quickly due to its small capacity, and the surface area and thermal conductivity of the aluminum foil is high, so any heat should dissipate quickly.

By using the dollar store alarm module, I was also able to tie a second string to the magnet that trips the alarm as the string winds around the shaft. Inside the module is a crude reed switch that opens when the magnet is removed, and closes when the magnet is near. The alarm sound itself is optional, and the trap will work without turning the module to "on" position since it draws its power directly from the batteries. But since the trap should only be used when I am at home (such as when I am far from the trap or if I am sleeping when nocturnal mice are active), the alarm will let me attend to the trap quickly, causing any brief stall conditions to be of no concern while also allowing me to make sure the animal doesn't escape. If I wasn't home, for instance, the animal could be trapped for a long period of time with limited air and the motor could stall out for a long period of time--both are scenarios to be avoided.

I tried cutting a tiny slit in the foil and tying a third string to the foil to break the electrical connection automatically when the motor reels in the string, but it just got jammed and didn't have enough force, causing even more resistance by making the foil circuit trace more narrow. So even if I switched to something thinner like fishing line that may cut completely through the foil, it is still not a good idea, in my opinion, having the potential for jamming and heating up, so I felt that it was safer to just allow the battery to drain through the stalled motor winding until I reach the unit to disconnect power.

Real-World Experience and Insights

If there is more than one mouse, the trap can get dirty with reuse, a disease hazard, so I found that a better design is to tape a disposable foil switch assembly to a cardboard lid and then lay this lid flat atop the main cardboard base, clamping the circuit in place. Then, when the bin falls, all I have to do is tape the remaining 3 edges of the bin to the lid, tear off or un-clamp the old foil traces, carry and eject the mouse, carefully dispose of the lid and old foil circuit, and sterilize the bin with a bleach solution. To reload the trap, a new lid and circuit are then placed on the base and then re-clamped. A lid assembly only requires cardboard, foil, toilet paper, tape (and cheese), so I was able to quickly create 3 of them ahead of time. Here you can see my first disposable lid taped atop the main base, and I also decided to replace the old alarm with a new alarm that I ordered online (they were just over $2 apiece) since the old alarm's reed switch was not reliable:

I didn't use any solder this time, and this newer alarm has a slide switch that can be placed in two modes, "door/window entry alarm" or "door/window open reminder", and this second mode, the open reminder, simply double-beeps a high-pitched sound about once a second. It is not as noisy as the main siren alarm, which may be less frightening for the mouse, yet still very audible as an alarm.

Both sharp cheddar cheese and havarti cheese worked well for me as bait. I didn't need to employ any peanut butter. Cheese caught the mice within only a few hours after I set the trap at night.

I tried covering the long panhandle wires with paper, thinking that a mouse might be fearful of walking across the silvery traces, but this was not the case--the mice didn't care and went for the cheese in both cases.

I noticed that if I didn't set the stick properly and vibration or something hit it and caused it to fall, the alarm wouldn't go off, which is to be expected, disabling the trap with the cheese inside. A good way to verify whether the stick slipped or if a mouse actually triggered the trap is to see if the string is wound around the shaft, a positive sign. That's why the stick in the photo at the top of this page is wide and not something like a toothpick. The wide base helps to add lateral stabilization that makes it less wobbly and more reliable.

If the batteries are weak and the mouse only briefly touches the switch, the stick might not pull fast enough and the bin can fall on top of the fallen stick, allowing the mouse to wedge through this gap and escape. So fresh batteries are more reliable. The insects, spiders, and centipedes in my house do not seem to be heavy enough to trigger the trap, since the foil "moat" is supported on all sides by the toilet paper, but it is possible a heavy insect like a beetle or cockroach (which I don't have) could also set off the trap, since the foil is very flexible.

If the trap is set for several weeks, the duct tape that I use tends to peel away over time, so it occasionally has to be pressed down again to ensure the motor is held fast to the cardboard base and also to ensure that the bin hinge is still intact.

Ideally, having a remote alarm (like a WiFi ESP8266 module) to alert me without blaring next to the trap, or having an alarm that shuts off after a few seconds, would reduce scaring the mouse, but this would require more materials, planning, and time.

The bin that I used has no air holes, which seems beneficial at first, since air holes make exposure to any airborne viruses more likely, but the downside is that when the trap falls, air pressure forces out air around the rodent, so in my case, I have to wait until the air settles and not inhale when I tape it shut until it is airtight, and then free the animal later. Luckily, the bin falls quickly and the slamming noise and alarm occurs at the moment the mouse would get scared, so if it does urinate, this would occur after the bin is closed. A cardboard divider could also be vertically taped in place near the end of the lid, forcing the air sideways when the bin falls, away from the reusable parts like the motor and alarm, to minimize spread of pathogens. If the bin does have air holes at the top, they could perhaps be taped over once the mouse is trapped and carried away, but since the bin would be inverted, any urine could leak through the tape, so I'm not sure if the addition of air holes would make it any safer.

In my experience, though, an opaque bin and no alarm resulted in a much calmer mouse, but that means that I must be nearby to hear the bin fall or else the animal could eventually suffocate due to lack of air holes.

Thankfully, there were no cases of hantavirus reported in Missouri, where I live, in 2018, according to the CDC↗ (the data at the time of this writing in April 2020 has not yet been published), and only a few species of mice and rats in North America are known to carry it at this time. The most dangerous time for transmission to humans is when the animal is still alive and in the home, with recent excretions/secretions that could become airborne, but also according to the CDC, the virus can live for several days↗ in the environment, even after the mouse has been removed. So its important to not agitate or inhale the dust afterwards, especially if it hasn't been that long after the animal was trapped. The CDC also has a general article about how to clean up after rodents on their rodents page↗ but their Facts About Hantaviruses brochure, mentioned earlier, is more specific to that particular virus, one that is more of a concern to me. Of course, of greatest concern was the historic pandemic of a different virus taking place at that very moment, but this was an additional variable that came at a bad time.

I also found that, logistically, it was better for me to set the trap about an hour before daylight and then drop off the mouse in the morning daylight, since catching a live mouse at, say midnight, meant that I would have to drive to a dark, remote woods around midnight, not an ideal situation in many ways, especially during the stay-at-home order.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this was the simplest design that I could come up with in a short time frame during an unusual period in US history when my options were limited. It used the household materials that I had on-hand (foil, tape, string, stick, cardboard, a heavy plastic bin, a dollar store or two-dollar alarm, binder clips, toilet paper, DC motor, and cheese), and it took me about an hour to create from conception to actual use, including finding the motor and fixing the reed-switch in my first cheap alarm (which took up most of the time). This was a quick and inexpensive project that is not a model for a proper disease-resistant trap designed by engineers and medical experts. However, having no wild rodents in the home is safer than having wild rodents in the home, so it was beneficial for me. As alluded to above, there is much room for improvement in reliability, providing better safety, and also in keeping the animal calm, but ease of construction, cost, and materials were not a concern for me; a soldering iron is not required, and the single-use, disposable materials for a disposable lid/circuit assembly are minimal. Because I tend to have electronic equipment on hand (along with lots of cheese), it was easiest for me, whereas coming up with a purely mechanical trap in short order might be easier for someone else.